|

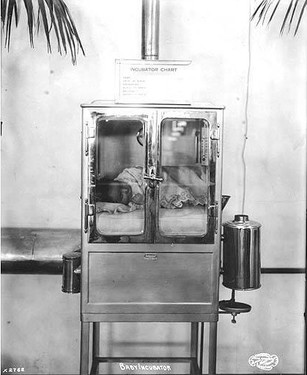

By: Elizabeth Payne It is hard to believe that only a century ago, most sickly and premature infants were sent home from the hospital without any special interventions; many of these children did not survive past their first birthday. The first neonatal intensive care units did not even appear in American hospitals until 1922; however, special care methods for infants began to be developed in the late nineteenth century. The Pre-NICU Era (up to the 1950's) Pierre-Constant Budin (November 9, 1846 – January 22, 1907) Pierre-Constant Budin (November 9, 1846 – January 22, 1907) Pierre-Constant Budin, a French obstetrician, was a pioneer in the care of at risk babies and devoted his career to reducing infant mortality. He encouraged educating new mothers about proper nutrition and hygiene for their babies, and knowing the risks contaminated cow’s milk could pose to newborns, urged the use of breast milk instead of cow’s milk, and believed that sterilized cow’s milk should be used if breast milk was insufficient. He also brought gavage- the process of feeding through a tube that went directly to the stomach- into the spotlight, helping premature infants who were unable to feed normally receive the nutrition they needed. Budin started his career as an assistant to Etienne Stephane Tarnier, another French obstetrician instrumental in the development for neonatal care. Infants that are born too early are often incapable of producing their own heat, and incubators help keep these babies warm and allow them to use their energy to grow and gain weight. Tarnier recognized this, and developed a crude isolette- a wooden box with a glass lid and a hot water bottle inside- to put premature infants inside of. Tarnier’s work contributed to a 28% decrease in infant mortality over three years at the French maternity hospital he worked in. Tarnier’s technology was picked up by a student of Budin’s, Martin Couney, who used considerably less conventional methods to help popularize special care for premature infants outside of France.  At the turn of the century, many hospitals in both America and Europe did not allow technology such as incubators to be used within their walls. Couney, however, recognized the potential of incubators for helping premature babies. Dr. Couney offered this type of treatment for premature infants free of charge; it was paid for through admissions. Dr. Couney displayed the babies in a sideshow at Coney Island starting in 1903, and charged onlookers twenty-five cents apiece to come in and view the babies and the technology keeping them alive. Similar sideshows were set up in Europe as parts of fairs and expositions, including the 1933 New York World’s Fair and the 1939 Chicago World’s Fair. Although the practice of displaying premature infants for money is certainly morally questionable, it helped pave the way for modern neonatal intensive care. Dr. Couney died in 1950, shortly after American hospitals began to use incubators to care for premature babies. Formation of the Modern NICU (1950s-1970s)Doctors and scientists began writing on the care of premature and sickly newborns as early as the seventeenth century; however, it was not until 300 years later that these babies began to receive special care in hospitals. Until the mid-twentieth century, most of these children were sent home without medical intervention; occasionally, they would have a nurse come home with them. It was not until after World War II that hospitals began to create Special Care Baby Units, the precursors to modern NICUs. The creation of special care units for infants was sparked by the realization that heat, humidity and a steady supply of oxygen could increase the survival rates of sickly babies, meaning that hospitals could intervene to help babies live as opposed to just sending them home. Hospitals were initially reluctant to adopt incubators because of their cost, the fact that they limited access to the infants, and the lack of evidence of their effectiveness. Dr. Couney’s exhibitions brought awareness to the effectiveness of the incubator, which encouraged hospitals to adopt the technology. This was further encouraged by the invention of the Hess Incubator by Dr. Julian Hess at the Reese Hospital in Chicago; in addition to providing heat and humidity for babies, the Hess Incubator delivered oxygen to the infants. The following decade, incubators with clear plastic walls were introduced, allowing doctors and nurses to easily see and access the babies. At this time, doctors were beginning to fully realize the danger that infection posed to newborns, especially premature babies. However, the way infection spread was severely misunderstood; it was thought that the biggest risk to a baby was another baby in the nursery. No one thought that a baby could get sick from a healthy adult. Dr. Louis Gluck was instrumental in proving this line of thought wrong. Along with Sumner Yaffe, Norman Kretchmer and Harold Simon, Gluck performed a series of experiments that involved two sets of babies; one washed daily, the other ones not. They would take cultures from both sets and compare them, and it became evident very quickly that the washed babies had fewer pathogens. To show that the children had a low risk of catching diseases from each other, Gluck began keeping the washed and unwashed children in the same nursery- at the time, keeping more than one premature infant in one room was considered a risky idea. This study included about 25,000 babies, and was never completed- the difference in the health between the two groups became so apparent that nurses began washing all of the babies regularly. It was shown that regardless of nursery mates, a baby who was washed regularly was much less likely to become ill than one who wasn’t; according to Gluck, there was “an 8 to 1 difference in acquisition of staph anyplace”. Gluck observed that the biggest issues was getting visitors and staff to wash their hands; to this day, this remains one of the biggest threats in the NICU. After his research convinced him that infections were more likely to be caused by poor hand hygiene than by other infants, Gluck redesigned the special care nursery, and encouraged the use of isolettes and incubators all in one room as opposed to keeping babies sectioned off in isolated cubicles. This allowed doctors, nurses and other caretakers to easily access and tend to the babies. Gluck additionally designed the L/S ratio test, which determined the maturity of infant’s lungs and therefore their chances of developing certain respiratory diseases. Because of these accomplishments, Gluck is often hailed as the father of neonatology. The Contemporary NICU and Family Involvement  Up until the 1970s, there was a very heavy emphasis on using machines to help at-risk neonates and very little on the involvement of the family. However, this began to change in the 70s. The Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Assessment Program was developed by Heidelise Als, which encouraged family involvement and individualized plans for each baby. The program reduced the number of ventilator days required for children and improved the outcomes of graduates. In this same decade, fathers obtained “nonvisitor” status in the NICU, allowing them to stay with their children outside of normal visiting hours and increasing a father’s role in caring for his baby. The importance of the bond between mothers and babies was understood and maternal-infant bonding was also encouraged at this point. This became even more heavily emphasized in the next decade with the advent of kangaroo care- skin to skin contact between mother and child to promote bonding, stabilize the baby’s breathing, heart rate and body temperature, and help the baby gain weight and grow. Kangaroo care is now encouraged for all parents, regardless of sex. Parental rooming-in- allowing parents to spend the night in the same room as their child- also was established in the 1980s, and older siblings became more involved in the care of babies; at this point, many hospitals established visiting policies for siblings. This allowed the whole family to help care for the baby and reduced the need for parents to look for childcare for their older children. Other family-centered resources were also established, such as support groups and antepartum consultations, helping families connect with other families who understand their struggles and helping prepare families for the difficulty of having a child in the NICU in the case of an at-risk pregnancy. In the 1990s, the increase of technology to care for premature infants as well as an increase in professional knowledge about premature infants gave hope to babies who in previous decades may have been considered lost causes. Babies as young as twenty three weeks gestational age and as small as 500 grams- were successfully treated. Improvements in nutrition management and new technology allowing for precise fluid delivery, the maintenance of temperature and proper ventilation management all contributed to helping these very small infants survive. Care has continued to improve, and the survival rate for babies born at twenty-three weeks gestational age is now at 33%; babies born at twenty-four weeks have a survival rate of about 65%. Survival without any major health complications has also increased. These increases show hope for premature babies and their parents, and trends indicate that survival rates will rise even more in coming years. With increasing technology and awareness, survival for premature and sick infants is slowly turning from an exception into the standard. References

"Babies On Display: When A Hospital Couldn't Save Them, A Sideshow Did." NPR. Accessed August 13, 2015. Gluck, Louis. Interview by Gartner, Lawrence. February 21, 1997 http://www.nytimes.com/1997/12/15/us/louis-gluck-73-pediatrician-who-advanced-neonatal-care.html Horn, Lucille. Interview by StoryCorps. Fountain, Henry. "Louis Gluck, 73, Pediatrician Who Advanced Neonatal Care." The New York Times, December 15, 1997, Obituary sec. Accessed August 12, 2015. http://www.nytimes.com/1997/12/15/us/louis-gluck-73-pediatrician-who-advanced-neonatal-care.html. Jorgensen, Anne M. "Born in the USA- the History of Neonatology in the United States: A Century of Caring." Accessed August 13, 2015. http://static.abbottnutrition.com/cms-prod/anhi.org/img/Nurse Currents NICU History June 2010.pdf. Pearson, C. (2015, September 8). Survival Rates For Micro Preemies Continue To Improve. Accessed September 9, 2015. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/survival-rates-for-micro-premies-continue-to-improve_55eed4fce4b093be51bbf26c Yaffe, Sumner, Lawrence Adams, Duane Alexander, L. Joeseph Butterfield, Louis Gluck, George Little, Mildred Stahlman, Mitzi Duxbury, Carol Gartner, Lawrence Gartner, and Philip Sunshine. "Neonatal Intensive Care: A History of Excellence." Www.neonatology.org. October 7, 1985. Accessed September 3, 2015. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed